Columbia River Basalt Group–outrageous!

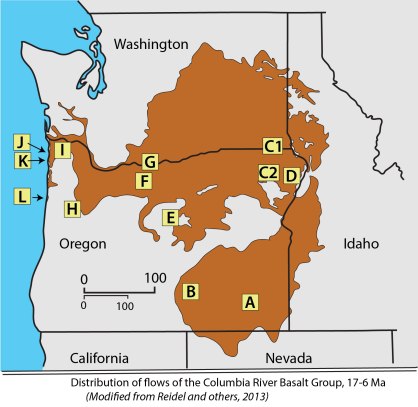

I can’t stop thinking about the Columbia River Basalt Group–the series of basalt flows that blanketed so much of my state of Oregon about 15 million years ago. Abbreviated as “CRBG”, it covers a lot of Washington too, as well as parts of western Idaho and northern Nevada. If you’re driving across those parts, you’ll likely travel miles and miles and miles over basalt basalt basalt –and that causes some people to say (mistakenly) that it’s boring. Some geologists even get grumpy about it because it covers up all the older rock. Outrageous!

Lava flows of the CRBG in northern Oregon and Mt. Adams of southern Washington. With views like this, how can you say the CRBG is boring? (Photo “F” on map below.)

But of course, the CRBG is outrageous for a whole host of other reasons. For one thing, it really is huge: it covers an area of more than 77,000 square miles with a volume of more than 52,000 cubic miles –that’s more than 50x the volume of air between the north and south rims of the Grand Canyon! Really—the National Park Service estimated the volume of “Grand Canyon Air” to be about 1,000 cubic miles. It also erupted over a fairly short period of time: from about 17 million years ago to 6 million –but 96% of it erupted between 17 and 14.5 million years ago.

And… most of it erupted from fissures in eastern Oregon and Washington –the roots of which are now preserved as dikes. And… many of the lavas made it all the way to the Pacific Ocean. And… (here’s the outrageous part), on reaching the Pacific, many of the flows re-intruded into the existing sediments and sedimentary rocks along the coastline to form their own magma chambers, some of which were thousands of feet thick! AND… some basaltic magma from those chambers then re-intruded the country rock to form dikes –and some even re-erupted on the seafloor!

All these outrageous details. Now think about them for a moment. They really happened. That’s what I find so wonderful and amazing about geology. We learn all these things and we put them in some part of our consciousness that doesn’t really let them soak in –but once in awhile they do.

Finally, the CRBG is beautiful and forms beautiful landscapes! Below are some photos to illustrate it, from feeder dikes in eastern Oregon to sea stacks eroded from a giant sill on the coast.

And I’ll save my snarky comments about young earth creationism for another post.

–and at the bottom, I’m adding a short glossary to explain some of the terms.

Ok… the photos!

Photo A. Steens Mountain and Alvord Desert. The CRBG started with eruption of the Steens Basalt about 16.7 million years ago, which makes up the upper 3000′ or so of Steens Mountain, shown here. Steens Mountain is one of our state treasures –it’s a fault-block mountain, uplifted by Basin-Range extension along a normal fault along its eastern side.

Photo B. Steens Basalt at Abert Rim. Like most of the CRBG, The Steens basalt covered outrageously huge areas. It also makes up the cliffs above Lake Abert about 75 miles to the east. Called Abert Rim, the cliffs are also uplifted by a big normal fault. Lake Abert occupies the downdropped basin. And much of the Steens basalt consists of this really distinctive porphyry with outrageously big plagioclase crystals!

Photos C-1, C-2. CRBG dikes. One reason we know that the CRBG erupted from fissures is that we can see their roots, as dikes cutting through older rock. C-1 shows a dike cutting through previously erupted basalt flows in Grande Ronde Canyon, Washington; C-2 shows some narrow little dikes cutting accreted rock of the Triassic Martin Bridge Limestone. Photos 5 and 6 of my last post shows some aerial photos and describes this area in more detail.

Photo D. Imnaha Canyon. The next major unit of the CRBG is the Imnaha Basalt, followed by the Grande Ronde Basalt. Both these units erupted from sites in northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. This view of Imnaha Canyon in Oregon shows the Imnaha Basalt near the bottom and the Grande Ronde Basalt at the top.

Photo E. Picture Gorge Basalt at the Painted Hills. And the next youngest unit of the CRBG was the Picture Gorge Basalt, shown capping the ridge in the background. Unlike most of the CRBG, the Picture Gorge Basalt originated in central Oregon, not too far from here–there’s a whole swarm of dikes near the town of Monument, Oregon.

The colorful hills in the foreground make up the Painted Hills of John Day Fossil Beds National Monument, another of our state treasures. I like this photo because it gives a sense of what lies beneath the CRBG –and the John Day Fossil Beds are outrageous in their own way–but save that for another time.

Photo F. Lava Flows of the CRBG and Mt. Adams, a modern volcano of the High Cascades in Washington. See the first picture at the top of the post!

Photo G. Wanapum Basalt near The Dalles. This exposure of the Wanapum Basalt, which overlies the Picture Gorge Basalt, tells the story of the CRBG as it flowed into and filled a lake along the Columbia River some 15 million years ago. At the bottom of the flow, pillow basalt formed as the lava poured into the lake, while the upper part of the flow shows the columnar jointing typical of basalt that flows across land. What’s more, this exposure lies less than a mile off I-84 in The Dalles, Oregon. See page 251 of the new Roadside Geology of Oregon for another photo and more description!

Photo H. Upper North Falls, Silver Falls State Park, Oregon. This wonderful state park hosts about a zillion waterfalls that spill over cliffs of CRBG, 14 of which lie in the main river channels of the north and south forks of Silver Creek. The falls depicted in this photo are 136 feet high!

Upper North Falls at Silver Falls State Park. The roof of the alcove consists of Wanapum Basalt, the bedrock near the river consists of Grande Ronde Basalt.

Notice that the picture’s taken from behind the water. The trail goes into a big alcove, so it’s easy and safe. The alcove formed because this particular waterfall crosses the contact between the Wanapum Basalt and the underlying Grande Ronde Basalt –and there is a 10-20′ thick, easily eroded, sedimentary unit between the two. Remember the Grande Ronde Basalt –from Photo D in northeastern Oregon? Here it is, just east of Salem!

Photo I. Saddle Mountain, northern Coast Range. Here starts the truly outrageous part of the CRBG story. Saddle Mountain, the highest point in the northern Coast Ranges, consists almost entirely of the rock on the right: brecciated pillow basalt, full of the alteration mineral palagonite. Apparently, the basalt started to flow into the ocean at about here, formed pillows and fragmented like crazy in the water-lava explosions.

But! These flows were likely confined too –such as in a submarine canyon–which allowed them to develop enough of a pressure gradient to intrude downward into bedding surfaces, faults, and fractures of the Astoria Formation. The diagram below illustrates the process in cross-section. The diagram also give a context for photos I-L.

Photo J. Sea stacks of intrusive Columbia River Basalt Group at Ecola State Park. Some of the magma chambers were several thousand feet thick and are now exposed as gigantic sills along the coast. One such sill is Tillamook Head, of which Ecola State Park is a part –and it’s eroding into the sea stacks you can see in the distance.

Photo K. Haystack Rock at Cannon Beach, OR. Go figure, one of our iconic state landmarks is an undersea volcano? You can actually walk out to this thing at low tide and see lots of pillow basalt and dikes intruding the Astoria Formation. The smaller sea stacks are part of the same complex.

Photo L. Seal Rock, Oregon. Seal Rock is the southernmost exposure of CRBG on the coast –and it too, is intrusive. It’s a big dike that trends NNW for about a quarter mile out to sea. And along its edges, there are smaller dikes that you can see intruding the Astoria Formation, such as in the smaller photo. The arrow points to where you can see the small intrusion, at low to medium tides.

Some Terms:

dike: a tabular-shaped intrusion that cuts across layering in the surrounding rock. Imagine magma flowing along a crack and eventually cooling down and crystallizing. That would form a dike. A feeder dike is a dike that fed lava flows at the surface.

normal fault: a type of fault along which younger rocks from above slide down against older rocks below. They typically form when the crust is being extended.

porphyry: an igneous rock with larger, easily visible crystals floating around in a matrix of much smaller ones.

sill: an intrusion that runs parallel to layering in the surrounding rock.

Some references:

Reidel, S.P., Camp, V.E., Tolan, T.L., Martin, B.S. 2013. The Columbia River flood basalt province: stratigraphy, areal extent, volume, and physical volcanology. In The Columbia River Basalt Province, Geological Society of America Special Paper 497, eds. S.P. Reidel, V.E. Camp, M.E. Ross, J.A. Wolff, B.S. Martin, T.L. Tolan, and R.E. Wells, p. 1-44.

Wells, R.E., Niem, A.R., Evarts, R.C., and Hagstrum, J.T. 2009. The Columbia River Basalt Group—From the gorge to the sea. In Volcanoes to Vineyards: Geologic Field Trips through the Dynamic Landscape of the Pacific Northwest, Geological Society of America Field Guide 15, eds. J.E. O’Connor, R.J. Dorsey, and I.P. Madin, p. 737-774.

Some links:

Roadside Geology of Oregon

Geology pictures for free download

Geologic map of Oregon

Beautiful. And Image A seems to be showing fracture on at least two different scales, perhaps three, less regular than the Giants Caueway that I blogged on at http://wp.me/p21T1L-oc More rapid cooling? Less depth? I’m sure there must have been work on this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Paul! Yes… isn’t that cool about those fractures? I’ll have to have a look back at your Giants Causeway story.

LikeLike

Marli- another great post. Thanks.

I used to have a job that required I traverse the CRBG several times a year to make sales calls at (contaminated) industrial facilities. Astoria to Zillah. Bend to Boise. Coeur d’Alene to Camas. The Dalles to Davenport. Ephrata to ….

The gobsmackingly awesomeness of the CRBG was one of the major reasons that I decided, in my mid-40s, to hang up my saddle, send my pony off to pasture, and settle down to go to college to get a graduate degree in geology.

Geology enthusiasts everywhere celebrate when you post words and photos, Marli. Thanks.

(One tiny edit: in the second paragraph, you wrote, “Really—the National Park Service estimated the volume of “Grand Canyon Air” to be about 1,000 square miles.” Should that be CUBIC miles?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Matthew! And thanks for pointing out that mistake–which is now fixed!

LikeLike

I love your passion! So much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Alyse!! I’m glad you saw it!

LikeLike

Marli, again, many thanks for your enthusiasm and knowledge.

Geological processes grind along in a stable, predictable manner, it would seem. What stabilizes (governs?) this process? How is equilibrium maintained so that, on a global scale, we don’t see such awkward oddities as 52, 000 cubic mile sink-holes, or land forms that sink out of sight under their own weight?

I hope the question makes some sense . . .

Larry Trippett

LikeLike

Hi Larry–thanks for the comment! As far as your question goes though, it’s probably beyond my expertise to give a really good answer –but I know of one study that argued the rise of the Wallowa Mtns was a response to the eruptions. By depleting the upper mantle of magma, it actually caused the roots to be more buoyant. Hales et al., 2005, Nature,v. 438: 842-845.

LikeLike

Thanks, Marli! Found a cc of Hales, et al., 2005, Nature.

Larry

LikeLike

I used to have a job that required that I traverse the CRBG several times a year to call at (usually contaminated) industrial sites. From Astoria to Zillah. From Bend to Boise, from Coeur d’Alene to Cle Elum, from The Dalles to Davenport, from Ephrata to….

The gobsmacking awesomeness of the CRBG is one of the main reasons I decided, in my mid-forties, to hang up my saddle, put my pony out to pasture, and go to college to earn, eventually, a MS in geology.

Geology enthusiasts everywhere celebrate when you post more words or photos, Marli. Thanks.

(One suggested edit: you wrote in the 2nd paragraph, ‘the National Park Service estimated the volume of “Grand Canyon Air” to be about 1,000 square miles…’ Should that be CUBIC miles?)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the nice words! and thanks for finding that mistake! I’ll get it fixed right away…

LikeLike

Facinating…regarding creationists, the Ken Ham vs Bill Nye debate was revealing.

LikeLike

Have a look say on google images at Niagara Falls in Oregon – wonder if it is CRB? It is east of Mt Hebo and might perhaps be part of the Tillamook flows like Cape Lookout

LikeLike

Thanks for the note –That’s a great place! I went there last fall and actually took a sample of the rock. But it’s andesite of the western Cascades –not CRB.

LikeLike

Pingback: Touring the geologic map of the United States | geologictimepics