Picture of the world in a sidewalk

Need a quick dose of geology? Go outside and look at a sidewalk. These human-made rocks offer a lot –from insights into weathering and erosion to regional geology and Earth History.

When I was 19 years old and just entering the geology major, I used to marvel at how sidewalks cracked. In front of me, almost in real time, geological weathering processes were at work, mostly through growing tree roots, differential settling of a sidewalk’s base, or a host of other processes that in Colorado typically included frequent freeze-thaw cycles. At the same time, other processes, aided by the water trickling into the cracks, were breaking down the concrete chemically. Suddenly, abstract concepts of physics and chemistry became real. I transformed from a science phobe to a science geek.

I’m still hooked on sidewalks. Not as much on their cracks, although they still fascinate, but the concrete itself. Consisting of gravel and sand—collectively called aggregate—as well as cement, which binds it together, this human-made conglomerate tells stories of landscapes dominated by volcanoes to coastlines to deserts. You just have to look at it.

But the aggregate can be hard to see. It’s frequently hidden beneath a fine cement-rich zone called the “float”, which typically rises to the surface when the concrete is poured and workers smooth over its top surface. Through wear and natural degradation, however, the aggregate gradually shows through. Those cracks I used to admire also expose the aggregate and can even act as small fault zones, allowing one side to shift relative to the other. Where the shifting poses a hazard to pedestrians, city crews sometimes grind the protruding edges to reveal a beautiful mosaic of differently colored, rounded pebbles, surrounded by a finer matrix of sand and cement.

Each of those pebbles has a story. Consider the close-up photos above: the one on the left shows a rectangular chip I cut from a larger piece of concrete; the central photo shows the chip mounted on a microscope slide and ground thin so that it can transmit light (a “thin section”); the photo on the right shows a microscopic view of the little rectangular area in the other photos. It appears in all its glory below!

Study that image: a typical pebble encased in concrete that we typically pay no attention to –and it’s beautiful! How can it not tell a story? Notice how the pebble is made entirely of crystals, oriented in a random fashion, telling us it cooled from a liquid state—the hallmark of igneous rocks. And the crystals are so small, the rock must’ve cooled quickly –on Earth’s surface as a volcanic rock. In contrast, intrusive igneous rocks, which cool and crystallize beneath Earth’s surface, consist of larger, easily visible crystals. (see my post on rock identification for examples).

By the same reasoning, I can tell that the many dark gray to black pebbles—or the gray-greenish ones, all so common in the sidewalks where I live in Eugene, Oregon—are also volcanic. And it makes sense. Eugene gets most of its aggregate from a group of giant gravel quarries just north of town near the confluence of the Willamette and McKenzie Rivers. Those rivers drain the western Cascades, which was an active chain of volcanoes from about 40-5 million years ago, and the High Cascades, which are active today. These pebbles are now rounded because they were transported by the river. Before that, they formed parts of larger and much more angular rocks that broke off outcrops somewhere up the McKenzie or Willamette drainages. Those outcrops were part of the lava flows that built the range.

Those black pebbles are mostly basalt, which typically form in relatively quiet eruptions like those on Hawaii or Iceland. The gray-green ones are mostly andesite or dacite, which can reflect more violent eruptions, like what happened at Mt. St. Helens some 45 years ago. I also see some red-colored basalt pebbles—red because of iron oxidation—some coarsely crystalline intrusive igneous pebbles, and even some rare sandstone pebbles, all of which have sources in the Cascades. And there are plenty of rocks that are very fine grained and featureless and so practically impossible to identify. I had a geology prof in college who would call rocks like that “FRDKs” –or “Funny Rock Don’t Know”.

Of course, other rock types make up the Cascades, mostly ash flow tuffs, pumice fall deposits, and cinders, which are all volcanic. There is even some sandstone and shale. But these rocks tend to fall apart easily during the rigors of river transport and so appear only rarely in our sidewalks. So, my sidewalk only tells a partial story of the Cascades. Still, it’s not bad, given that my favorite “exposure” lies just down the street!

As the most used natural resource aside from water, concrete is pretty much everywhere humans live, so you can play this game just about anywhere you go. In fact, some of my favorite sidewalks are in southwestern Montana, where locally sourced gravel includes red, green, white, and tan quartzite pebbles. These pebbles come largely from rocks of the Belt Supergroup, which accumulated in a large inland sea between about 1.4 and 1.47 billion years ago. Rocks of the Belt Basin make up the incredible peaks and ridges of Glacier National Park in Montana. They extend all the way west to Spokane, Washington, north into Alberta, Canada and south beyond Salmon, Idaho. The bedrock erodes into such beautiful pebbles that it’s even sold in Eugene as “Rainbow Gravel”.

It’s the same with natural conglomerate. The pebbles and cobbles that populate the “clast content” of a conglomerate present a partial image of the landscape when those sediments were deposited. The base of the Kootenai Formation in southwestern Montana, for example, hosts a conglomerate that’s about 120 million years old. It’s full of chert and quartzite pebbles derived from the much-older Phosphoria and Quadrant Formations. Their presence in the conglomerate indicates mountain-building was taking place in the west about 120 million years ago because the two older rock units, once buried beneath more than 1000 feet of younger rock, had to be exposed in the source area.

In some cases, a particularly unusual rock type exists in the mix, which allows researchers to trace it back to its specific origin. In the Amargosa Valley of California–just east of Death Valley National Park—you can see large pieces of granite in conglomerate of the 15-11 million-year Eagle Mountain Formation. The granite is uniquely tied to exposed granites near Hunter Mountain, some 60 miles away, so we know that the river carrying the gravel had to drain the Hunter Mountain area. In eastern Oregon, the Goose Rock Conglomerate, which is some 100 million years old, contains cobbles that were derived from a granite source in Idaho some 100 miles to the east.

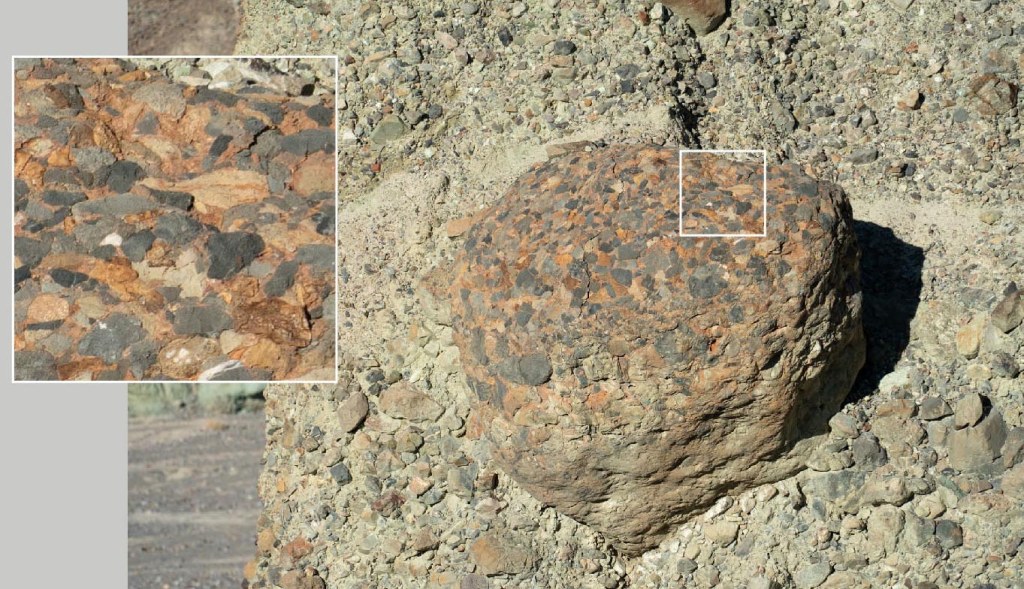

A few years ago, while scrambling around on some conglomerate in Death Valley, I found a boulder that itself was made of conglomerate: a conglomerate within a conglomerate! Think of its history. The clasts within the conglomerate boulder were made of a variety of sedimentary rocks, mostly limestone and dolomite with a few scattered quartzite pebbles. They originally formed during the older part of the Paleozoic Era, between about 400 and 540 million years ago or even before. Those were times when this part of North America was mostly submerged beneath shallow ocean waters, interrupted by brief periods of emergence. A thriving ecology produced thick deposits of lime mud on the sea floor, which formed the limestone and dolomite; deposits of sand, which became quartzite, formed during the periods of emergence.

Those pebbles, each with their own rich histories, were eroded and transported away from their original sites, deposited together, buried by more sediment, then compacted and cemented into the original conglomerate (step 2 below). As that conglomerate was re-exposed, probably because of some local uplift, it too eroded into loose rocks of varying sizes– and those boulders and cobbles were pieces of conglomerate. Some of those rocks were transported and deposited along with other sediments, which were compacted and cemented into conglomerate of the Furnace Creek Formation. The Furnace Creek Formation, which is only some 3.5 to 6 million years old, has been uplifted and tilted and is weathering and eroding today.

Everything at Earth’s surface eventually breaks down physically and chemically, exposed rock and sidewalks alike, which brings me back to my original fascination. We can see it happening. When sidewalks decay, we replace them with new concrete, starting the process all over again. While most of the worn, broken concrete now gets recycled, a lot doesn’t, and it ends up in our landfills, fields, streams, or beaches. Some of that concrete will get preserved along with other sediment, preserving an incomplete, yet intriguing picture of today’s world –and what came before.

Not that you’re dying for photos of sidewalks, but all these pictures are freely available as uncropped version on my geology photo website. If you type “sidewk” into the search function (red button), they’ll appear and you can download a copy!

Oh! And I wrote an earlier (short) essay about the conglomerate at the base of the Kootenai Formation in Montana if you’re interested.