Mountain in Transition

inside the crater of Mt. St. Helens

(click on images to see them at full size)

There’s a glacier in the crater of Mt. St. Helens—and unlike most other glaciers, it’s growing. Shaded by soaring crater walls and continually replenished by snow avalanches and rockfalls, it oozes forward more than 100 feet per year. At the sound of a loud crack, I look up at its steep front to see a bunch of rocks breaking free of the ice and tumbling downwards to rejoin their compatriots at the bottom. Soon, the ice will advance over them and they’ll be a part of the glacier again.

I’ve long been attracted to these landscapes, practically devoid of organic life but alive just the same. They evoke a sense of timelessness, a connection to Earth’s past, long before mammals and reptiles, let alone humans, colonized its surface. Besides this glacier, near-continuous rock fall and rising dust plumes, there’s a 1000’ tall lava dome that still puts out steam. Younger than many teenagers, the dome formed as sticky silica-rich lava extruded from a vent in the crater floor. It rose to within 800 feet of the highest part of the rim over a period of 5 years, from 2004-2008. It now towers over an older dome, which grew from 1980 until 1986, scarcely middle-aged by human standards.

My group is taking its lunch break. One person’s off shooting photos, a few are talking quietly, another’s inspecting some of the pumice and broken rocks that blanket this part of the crater. Our guides are conferring over our route. I feel lucky to be here, having been invited a few months ago to accompany the group to talk about the geology. The Mt. St. Helens Institute, the non-profit that organized the trip, does so under a special use permit from the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.

Looking northward to Spirit Lake and Johnston Ridge, I see a landscape of somber browns, yellows, and grays, decorated with greens. Most of those colors come from rock, either ancient bedrock or eruptive products from the big eruption in 1980. The greens though come from vegetation that is rapidly covering the lower elevations. On the way here, we walked over ashy fields spotted with prairie lupine, paintbrush and a host of other wildflowers I couldn’t identify, small stands of juvenile Douglas Fir and through the occasional jungle of alder.

Almost nothing in my view was spared the effects of the 1980 eruption. At 8:32am, May 18, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake caused the bulging north side of the mountain to fail as a gigantic avalanche, releasing pressure on the magma within the volcano, which naturally expanded northwards at supersonic speeds. Entire forests blew over in the scalding hot gas. 10 miles from the crater and forty years later, you can still see many of these trees lying down in formation, just like toothpicks. The failed north side of the mountain, all .67 cubic miles of it, ranks as the world’s largest debris avalanche in recorded history. I can see its path, marked by giant piles of rock called hummocks. Even here in the crater are deposits of the debris avalanche, forming towers of conical pointed hills more than 100 feet high.

I stoop down to look at a small plant. It’s all by itself, growing between loose, rounded pieces of pumice and undoubtedly rooted in more of the same. An early colonizer. If the crater floor were to remain undisturbed, more vegetation would creep in and eventually, this place would become lightly forested like other places nearby at this elevation. Of course, that’s unlikely here, with an advancing glacier and all the rocks falling from the rim.

Or more eruptions! Mt. St. Helens is, without question, the most active volcano in the Cascade Range, with more than a dozen smaller eruptions since the big one on May 18. And long before 1980 there were hundreds. The US Geological Survey closely monitors Mt. St. Helens’s ongoing activity as well as its geologic past to understand the volcano’s behavior through time. They define its history in terms of four distinct eruptive “Stages” that stretch back some 275,000 years. The most recent of these, the Spirit Lake Stage, started about 3900 years ago and is further divided into six eruptive “Periods”, each marked by multiple eruptions and separated by times of dormancy. One of these eruptions, between 3500-3300 years ago during the Smith Creek Period, dwarfed the 1980 eruption. And in the early 1480s, two eruptions of comparable size to the one in 1980 occurred just two years apart.

Shading the sun from my eyes, I look southward to the volcano’s rim, and I can see a whitish layer produced by these two eruptions. It’s called the “W Tephra”. More than 250 feet of rock now sits above it –all formed after 1480. And there used to be 1300 feet of rock above that, until it was blasted off in 1980—which means that in 500 years, Mt. St. Helens grew more than a quarter mile in height. Just before its cataclysmic eruption, its summit stood 9,677 feet above sea level.

It’s the myriad smaller eruptions that cause a volcano to grow, and in the case of Mt. St. Helens, they mostly produce lava domes instead of lava flows. As a college student, I had the hardest time visualizing a lava dome because the photographs I saw just looked like gigantic piles of broken rock. But that’s basically what they are, gigantic, dome-shaped, piles of rock. Imagine lava that is so viscous it can hardly flow, oozing out of a volcanic vent, and pushing aside or piling on top of earlier extruded lava, and cooling and breaking up in the process. By its very nature, silica-rich lava like the dacite of Mt. St. Helens is highly viscous. Silica molecules bond with each other to form interconnected networks, so the more silica in a lava, the more viscous it tends to be. Lower silica lavas like andesites contain fewer of those networks so they’re more likely to produce lava flows. Basaltic lavas contain even less silica and flow even easier.

Feeling a gentle breeze, I close my eyes and imagine this place sometime in the future. Two hundred years? Five hundred years? I picture the crater walls, slightly lower now, having steadily eroded through time, their debris gradually filling the crater. A couple large landslides have removed large fractions of one of the walls and piled their debris up against today’s modern domes. During this time, the mountain was largely dormant, but now a pulse of basaltic magma is working its way towards the surface, intruding the gray dacite domes along fracture surfaces as black basaltic dikes. Some of these dikes break through the top of the domes and spill out as basaltic lava flows, which flow a short way down and out of the crater. Mt. St. Helens awakens again, but this time, the lava is basalt so it awakens quietly.

I remind myself that this volcano hasn’t produced much basalt during its 275,000-year history. It doesn’t tend to “awaken quietly”, but more like some grumpy person who you’ve roused with a splash of ice water. Besides the numerous domes, its products typically depict violence: deposits of fallen ash or pumice, or pyroclastic flows, which consist of fast-moving ash, pumice and rock fragments mixed with hot gases. The only basalt lavas from Mt. St. Helens erupted during the end of the Castle Creek Period, which stretched from about 2500 to 1900 years ago. Ape Cave, the lava tube on the volcano’s south side, formed in these lavas, as did the steep rocky slopes we climbed on our hike into the crater. And there, low on the east crater wall, I can see the drama: black Castle Creek dikes slicing through light-colored rock of an older dacite dome. They’re overlain by dark-colored Castle Creek lava flows likely fed by the dikes below, just like my daydream.

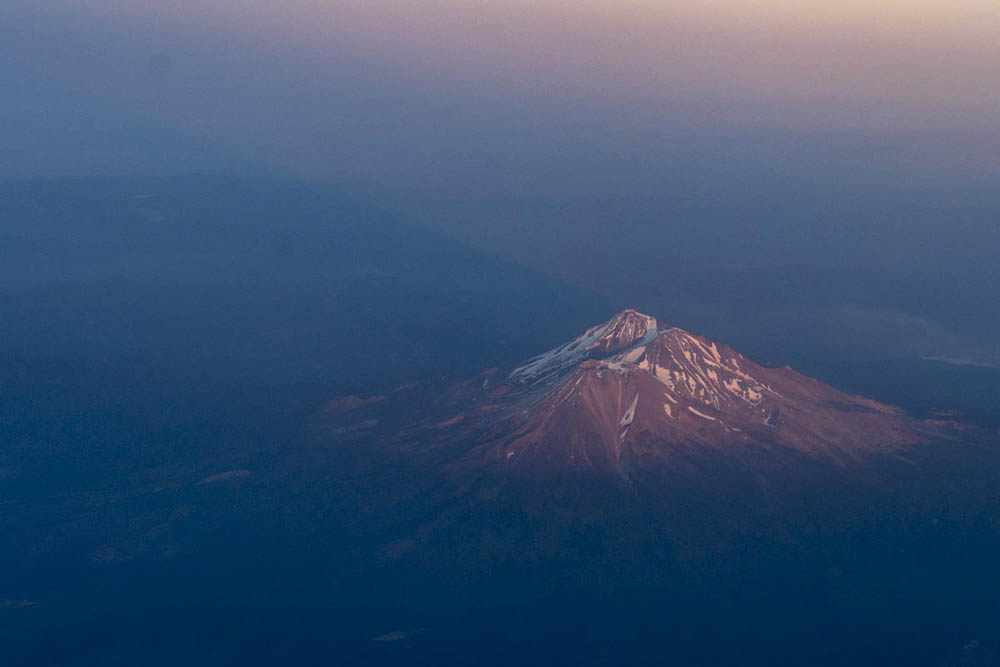

As we start our descent, I reflect on the ongoing Modern eruptive period. Before the first earthquakes on March 16, nearly everyone in the Pacific Northwest viewed Mt. St. Helens as a perfectly symmetrical and docile ice cream cone of a mountain. My college friend Michael longed to return home to Portland for long enough to climb it, partly because it offered such a wonderful glissade after summiting. Then less than two weeks after those first earthquakes, the first steam eruptions began. Then more earthquakes. Bulging of the northern edifice. Steam. Earthquakes. May 18.

We’ve learned so much since then! We’ve watched the Modern Period unfold with our own eyes as well as with a vast array of ever-evolving instruments. We can see the rich details of the volcano’s behavior to the point that researchers divide the last 40 years into two subperiods, defined by the formation of each lava dome. We’ve watched Crater Glacier evolve from a snowfield to a full-on glacier that itself has experienced major changes in its shape and behavior. We’ve watched the crater rim erode. We’ve watched vegetation recolonize a landscape that was suddenly rendered devoid of nearly all organic life.

Our group stops for a quick break at Forsyth Spring to absorb the flourishing willows, alders, and sounds of running water. I contemplate the earlier phases of Mt. St. Helens, reaching back to its origin as a series of lava domes 275,000 years ago. Those phases must have been as interesting and diverse as today, but we can experience them only through whatever preserved evidence we can find in the volcano’s deposits. We can’t taste the water or feel the freshness of new growth. Still, we can imagine it.

For this reason, I don’t think of today’s Mt. St. Helens as being “reborn” as it’s so often described. Sure, the vegetation is returning, but I can’t help but see it as incidental to the overall story of a volcano that’s always in transition. The 1980 eruption wasn’t an end point or a beginning –just an event that happened during a long eventful history. We’re experiencing just another moment, another transition, in this volcano’s cycle of life.

All photos freely available from geologypics.com. Click here for more photos of Mt. St. Helens and its geology. Type “Mt. St. Helens” into the search to see them all!

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.