Levels of Time

This essay first appeared in the April, 2024 issue of Desert Report.

I’m hiking up a closed road in Death Valley National Park to see a pile of gravel. I guess that’s one way to look at it. What some folks might view as a waste of precious time in this magnificent place I see as a vehicle for time travel.

Just 4 months ago in August, Hurricane Hilary dropped some 2.2 inches of rain on Death Valley—more than what typically falls here over the course of a year. With virtually no soil to absorb it, the water ran off immediately. It gathered in rivulets, confluenced into small channels, then larger channels, and finally streams that flash-flooded down canyons and alluvial fans. The flooding closed every road in the national park. It’s now early January, 2024 and this road up one of the fans isn’t supposed to open to cars for another two weeks.

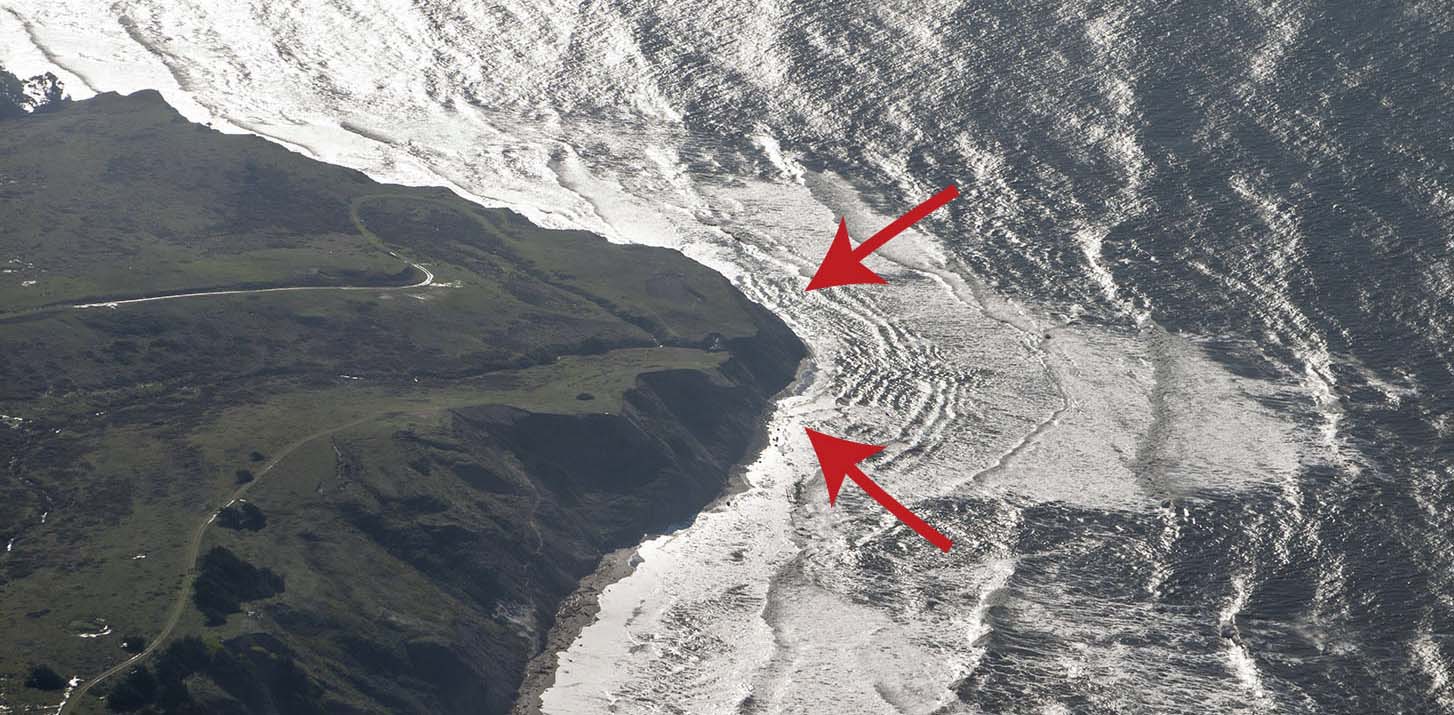

In just under two miles, I reach my destination, a low ridge extending eastward from the base of a hill. It was deposited by waves near the shoreline of a giant lake called Glacial Lake Manly, sometime between186,000-120,000 years ago. The ridge grew by fits and starts out from the hill as a spit, with waves obliquely slapping its front and moving the gravel out to its tip. You can see wave-rounded cobbles in the roadcut forming curved layers that slope towards the valley. They’re also scattered about on the top of the spit where I sit down and take in the view.

In front of me, the highway descends its gentle gradient to where I parked the car, nearly 200’ below sea level. From there, the floor of Death Valley is practically flat, continuing well past Badwater Basin some 25 miles to the south. When this gravel spit formed, Lake Manly, more than 50 miles in length and some 6-8 miles wide, filled the entire scene. At its high stand, I’d be below water because the lake’s highest shoreline reached another mile up the road. The gravel spit formed as the lake receded. Two smaller ridges lie just below where I sit and another very small one lies just above, marking different stages in its retreat.

Just like anybody, I wrestle with the ever-changing and fluid concept of time. Stopped highway traffic that delays my arrival by 15 minutes can seem interminable and I bemoan how quickly a year passes. I’ve heard countless people comment at how Badwater Basin is still flooded by water from Hurricane Hilary but when it all finally evaporates, we’ll probably describe the shallow lake as short-lived. This remnant of a giant lake that existed over 100,000 years ago takes my confusion to a new level. Was that a long time ago?

It seems so, but then I think of the mountains that enclosed the lake. They started rising some 3-3.5 million years ago—more than 20 times the age of the lake. I’ve always considered the mountains to be young, even going so far as to tell park visitors that Death Valley’s present landscape was “only about 3 million years old”. Compared to their rocks, many of which are older than 500 million years, that’s true. Some of the rocks are well over a billion years old.

Those rocks tell stories –about how they formed and about what’s happened to them since. I pick a cobble up off the spit. It’s a beautiful maroon color and made of tiny grains of quartz all mushed together. I suspect it came from the Zabriskie Quartzite, a distinctive rock unit that forms prominent cliffs throughout the region. Its sand was deposited mostly in a shallow ocean and various coastal environments during the Cambrian Period, which lasted from 539-485 million years ago.

I’ve studied geology my entire adult life and I still find it incredible that I can hold, in my own hands, a piece of the Cambrian sea floor. Each of the millions of tiny sand grains that make up this rock originated from some still-older rock and were transported by streams to the Cambrian shoreline. There, they were probably kicked around by coastal waves until getting buried by layers of more sediment, followed by more sediment for who knows how long –until circulating groundwater cemented the compacted grains together as layers of rock. In the Death Valley region, there are more than 10,000 feet of sedimentary rock on top the Zabriskie Quartzite and at least another 10,000 feet of sedimentary rock below. Each bedding plane in that sequence of rock was once the Earth’s surface.

And so much has happened to them since! Besides today’s mountain-building, driven because the earth’s crust in the region is extending, they’ve all experienced an earlier period of mountain-building by crustal compression. At the mouth of Titus Canyon just 20 miles northwest of here, those events folded the rock to where the sequence is completely upside down. Elsewhere, the rocks were intruded by granitic magma, while others were carried to depths of 15 miles or more and partially melted. And now, as today’s mountains erode, they shed rocks of all ages and types and sizes into their canyons, which get washed out onto the alluvial fans during floods.

From my perch on the gravel spit, I’m just a few feet above the alluvial fan. It’s unmoving and silent. The road will reopen soon, and tourists will once again drive past this spot without a second thought. But the myriad channels and wild assortment of rocks of the fan speak to a process that never stops. It will flood again. I see the whole fan in motion, with gravel streaming over the road, tearing up the asphalt, eventually burying or eroding the gravel spit. Today, this year, my existence—they all seem to diminish into the infinitesimal. I close my eyes and start walking downhill, deeper into the lake.

This essay came about from researching my forthcoming book: Death Valley Rocks! Forty amazing geologic sites in America’s hottest National Park, to be published by Mountain Press. (Sept, 2024)

Each photo (and >5000 more) is available for free download from my photography site, geologypics.com –just type the description or stock number into the search.

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.