Summarizing Death Valley’s Geology in 12 outtake photos

I’ve long been drawn to Death Valley. As a geologist, I can’t think of a better place to witness the incredible geologic history that shaped western North America –and as a photographer, I can’t think of a better place to capture images of what’s a mind-boggling array of geologic features.

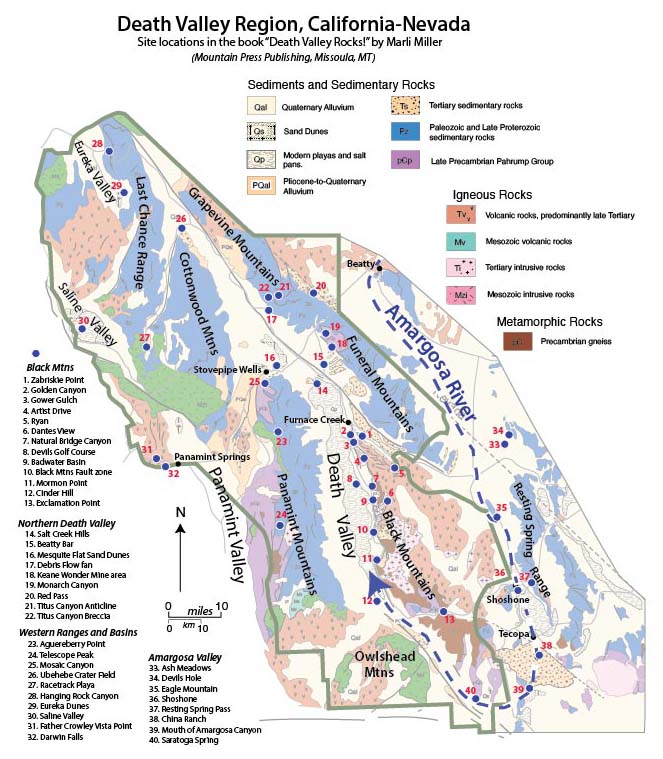

To that end, I recently completed a book called Death Valley Rocks! A guide to geologic sites in America’s hottest national park. It’s being published by Mountain Press and should be out in early July. The book covers 40 geologically amazing sites in the national park as well as the adjacent Amargosa Valley and will be full of color photos and maps –and (of course) many of my photos didn’t make the cut. Here are twelve of those outtakes, selected to present a general picture of Death Valley’s geology. You can click on any image to see it at a larger size.

The first photos reflect Death Valley’s modern setting, an actively evolving basin in the southwestern part of the Basin and Range Province. The valley is the terminus of the Amargosa River, shown as the heavy dashed blue line resembling a giant fishhook in the map. The river starts just north of Beatty, Nevada, and flows southward about a 100 miles through the towns of Shoshone and Tecopa before turning northward to empty into Death Valley. Without an outlet, all the water that reaches the floor of Death Valley stays there until it evaporates. As it evaporates, the water precipitates salt, producing a magnificent salt pan that is broken by myriad polygonal shrinkage cracks.

Read more…

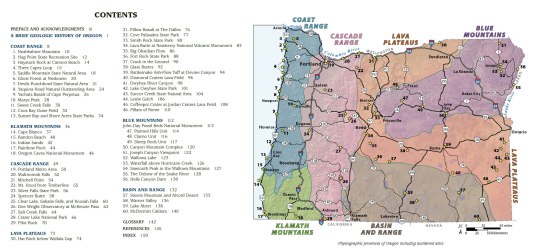

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.

From the geologic map, modified from Bishop and Smith, 1990, you can see how the brown-colored canyon-filling basalt, (called the “Intracanyon Basalt”) forms narrow outcrops within today’s Crooked and Deschutes canyon areas. It erupted about 1.2 million years ago and flowed from a vent about 60 miles to the south. You can also see that most of the bedrock (in shades of green) consists of the Deschutes Formation, and that there are a lot of landslides along the canyon sides.